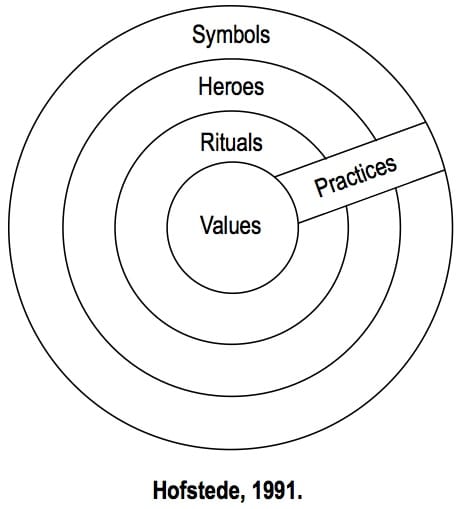

Elements of the Culture Onion

My last post gave a brief explanation of what culture is, the main takeaway point being that culture is all around us on different levels. The next logical question is, “Why should I care?” I’ll answer that in the next few weeks because we need to take a short detour – specifically, how would one analyse and assess the culture of a given group? The answer may lie in the culture onion.

Although cultures can be difficult to compartmentalise, try we must, and much smarter people before us have offered some suggestions. Let’s check them out and apply it on a fictional group – the Acme Inc. software development team._

_

(Source: Unfold Conflicts)

It’s helpful here to think of culture as an onion. The outermost layer is the Symbols layer. These are the visible signs of culture that even non-members can see. A good example is job titles, like how Acme’s developers are segmented into junior, intermediate, and senior software engineers.

Peel back the symbols layer and you might find the Heroes layer. These are the people that embody the whole culture, and is usually an aspirational figure. For example, one of Acme’s heroes is Vanushka ‘the Brave’, who worked all night that one time to get their Docker installation on Azure running again. Such heroics are praised and newcomers are told of how Vanushka saved the company’s reputation before the big launch.

Rituals come after the Heroes layer, and as the name suggests, it represents the habitual activities that occur without much thought (or are taken for granted). In Acme, developers mark the end of a sprint by having Friday afternoon pizza and drinks. It’s not a formalized procedure or mandated management practice – it is accepted that it “just happens”.

Cutting across the first 3 layers of the onion are Practices. They represent the activities that are performed regularly and are influenced by the Symbols, Heroes, and Rituals. For instance, Acme practices test-first development (ritual) and any developer who sneaks code in without a suitable test would get a swift rebuke from a Senior Engineer (symbol). After all, Vanushka is the aspirational figure (hero) that other developers look up to and it was unit tests that helped Vanushka troubleshoot the critical issue.

At the core, which all the previous layers inform and derive from, are the Values (also known as Paradigms). They represent the deeply held beliefs within the culture and are the hardest to identify, especially from the outside. They are usually quite basic in nature, but absolutely crucial in that it supports the rest of the culture. One of Acme’s paradigms is the importance of following process, as when coders who miss a unit test are called out. Another attribute valued by Acme is the dedication to getting work done at all costs, as when Vanushka spent all night fixing a critical issue.

The double-edged sword of Values is that they are ingrained and are difficult (some would say impossible) to change. Let’s say the unspoken practice of working late to fix production defects is seriously damaging developers’ work-life balance. Is it a simple matter of outlawing work after 8pm? The issue here is that the “get work done at all costs” ethic is a core value of Acme, and any person who attempts to change it will have to confront the cultural rubber band. This is a topic I will come to at a later stage when I write about culture change efforts.

The key point of my post is: culture is comprised of many elements and some are more ingrained than others.

Next week, I will present a model of analyzing culture that I personally found helpful to identify the different layers of the culture onion.