Cultural Web

A Cultural Web Analysis is another useful tool that helps tease out the constituent parts of an organisation’s culture. It builds upon the Onion Model of Culture mentioned previously, but has more concrete classifications that I found helpful. The Cultural Web was introduced by Gerry Johnson and Kevan Scholes, who were also writers of the excellent Exploring Strategy textbook I used for my Strategic Management course.

Once again we will apply it on the fictional Acme Inc. software development team so you can see how elements of the Onion Model translate (and get expanded) by the Cultural Web.

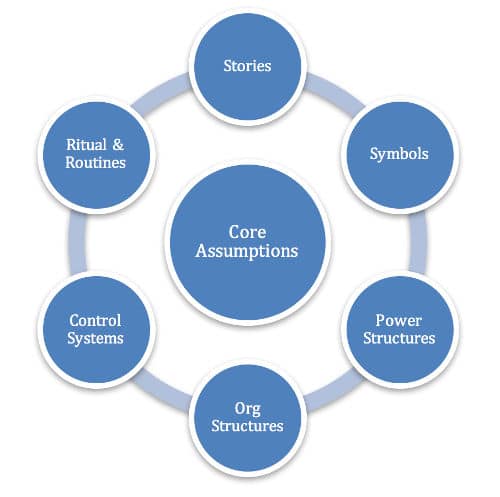

The Cultural Web consists of 6 elements that, taken together, define the “paradigm” of the organisation. Simply put, they are the core assumptions that people in the organisation take for granted. This is the hardest to analyse regardless of your membership status with the organisation – members find it hard to define things they do habitually, and non-members are not privy to the inner-goings that will reveal the paradigm.

The Cultural Web Analysis goes some way to propose a structured approach in identifying the “behavioural, physical, and symbolic manifestations of a culture” (all quotes in this post are from Exploring Strategy, 10th edition).

- Rituals and routines: Rituals are special events that emphasise important aspects of the culture, while routines are “the way we do things around here on a day-to-day basis”.

- Acme: A yearly ritual for Acme developers is to conduct an in-house code retreat that gives the developers a chance to try different development techniques and reinforce the power of pair programming and unit testing. This is largely due to test-driven development being a key routine that they practice everyday.

- Maps to Rituals and Practices in the Onion Model.

- Stories: They are tales told between themselves, outsiders, and new members, in order to explain why things are done a certain way. They highlight the “successes, disasters, heroes, villains, and mavericks” in the organisation’s past.

- Acme: The tale of how Vanushka saved the product launch is one that is often brought up when explaining why Acme does aggressive test-driven development. It is a story containing heroes, successes, and disasters.

- Maps to Heroes in the Onion Model.

- Symbols: “Objects, events, acts or people” that represent an idea larger than their functional purpose. For example, company cars serve a functional purpose but they also symbolise status and hierarchy for those who own one.

- Acme: Developers have a junior, intermediate, and senior ranks, which symbolise seniority and the influence they have on product decisions. In other words, the functional purpose of the job rank is to denote the experience of a developer, but it also confers power beyond its intended function.

- Maps to Symbols in the Onion Model.

- Power: Refers to the power structures in the organisation. Power is the “ability to persuade, induce or coerce others into following certain courses of action”. The book authors noted that “the most powerful individuals… are likely to be closely associated with… the long-established ways of doing things”.

- Acme: The job titles mentioned above are certainly a power structure. “Heroes” like Vanushka are also conferred power in influencing key architectural decisions, thanks to the stories that fuel his reputation.

- Maps to Symbols in the Onion Model.

- Organisational Structures: The “roles, responsibilities, and reporting relationships in organisations”. This is simply an organisational chart, but the key point is to look into why it is structured as such because it will reveal the power structures or other symbols.

- Acme: The development team is actually divided into 2 reporting groups, one for Software Architects, and another for Software Developers. The architects act as consultants, and the developers make the final decision on the best architecture for their needs. From this we can deduce that the power of architects is limited to the advisory stage, unlike most organisations where architects have veto-like power.

- Maps to Symbols in the Onion Model.

- Control Systems: They are the “formal and informal ways of monitoring and supporting people… and tend to emphasise what is seen to be important in the organisation”. A great example given in the textbook is about how public service organisations tend to emphasise how public moneys are used rather than the level of service provided, and this is reflected in the control mechanisms used.

- Acme: Peer code reviews are a control system used to ensure that Acme’s development practices are adhered to, especially the presence of unit tests. Besides that, 360-degree reviews form a small part of the annual performance evaluation.

- Maps to Practices in the Onion Model.

All of those six elements inform, and are informed by, the Paradigm. Mapped to the Values core of the Onion Model, they are the commonly held assumptions in the organisation. They tend to be very basic rather than specific. Looking back at the Cultural Web Analysis for Acme Inc., one might surmise that a paradigm of the development team is the importance of technical excellence through their aggressive unit testing practice and stories told. However, from that we can note a lack of focus on customer satisfaction, i.e. Acme might create the most perfect, bug-free software ever written, but does it actually meet the customer’s needs?

Now that you have a good idea of what a Cultural Web Analysis entails, I urge you to take a cursory look at your organisation, team, family, and yes, even yourself! Culture exists on the personal level all the way to the largest organisations, and being able to analyse it is the first step in planning for success. It shouldn’t take more than 30 minutes to do a first draft that fleshes out the main parts.

I will conclude this introductory series on culture next week by answering the question I previously posed – “Why should I care?”